The Maritime Ringlet

The Town of Beresford and its salt marshes are blessed with the host of a unique butterfly species, the Maritime Ringlet. This page will show you this neighbour, quiet, discreet but also fragile.

Note that this butterfly is found on the logo of the town, it symbolizes flight and freedom, but also our proximity to nature, its fragility and our duty to preserve it.

Beresford’s salt marsh is unique in the sense that it is home to an extremely rare butterfly: Coenonympha tullia nipisiquit, also called the Maritime Ringlet. Many studies have to come to identify the Maritime Ringlet as a threatened species by virtue of the provincial Endangered Species Act in 1996, and it was designated as an endangered species by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 1997.

The Maritime Ringlet is a dark ochre to ochre-brown butterfly with an ocellus on the forewing, that is, a spot resembling an eye. This trait is more developed and more widespread in the female. Very often you notice that the colour turns greyish brown at the edge of the front fender and almost the entire top of the rear fender.

As they age, males get darker and darker. The wings of the Maritime Ringlet have a wingspan of about 3.4 cm for males and 3.6 cm for females. The Maritime Ringlet is often confused with its cousin, the Tawny Satyr.

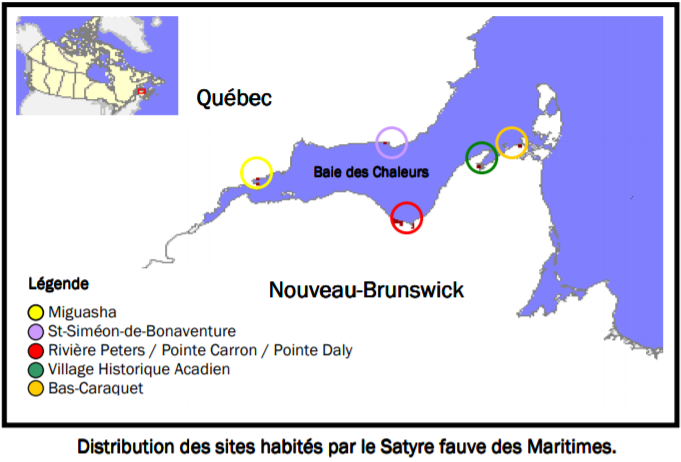

The Maritime Ringlet is a unique butterfly in many ways. First, it is one of only two butterfly species in Canada that lives exclusively in salt marshes, the other being the lilac-bordered copper (Lycaena dospassosi). To date, there are eight sites worldwide where the Maritime Ringlet is found. They are located in northern New Brunswick and eastern Quebec. They are located in northern New Brunswick and eastern Quebec. In New Brunswick, these sites are clustered around Chaleur Bay, with the largest population found right here in the Beresford Salt Marsh at the mouth of the Peters River. There are also two other settlements near Bathurst, one at Daly Point and a smaller one at Carron Point.

In the Quebec City region, three sites were identified, including two near Miguasha and another near the municipality of St-Siméon-de-Bonaventure. Recently, there has been another sighting of this butterfly in the Gaspé region, but few details are available. Despite the lack of data on the subject, it is believed that populations of the Maritime ringlet in Quebec are very small.

Like all species, the Maritime Ringlet has specific needs as to its habitat. First of all, it is found strictly in salt marshes where it can find the necessary plants for its survival; Sea Lavender (Limonium nashii) and Salt-Meadow cordgrass (Spartina patens). As for the Salt-Meadow cordgrass, it is vital for the caterpillar’s development, as it offers both food and shelter.

It has been noted that the size of the Maritime Ringlet population varies with the type of plants found in the salt marsh. The population size varies with the type of plants that are found within the marsh, as its density depends on the available quantity of Sea Lavender and Salt-Meadow cordgrass.

The Maritime Ringlet has four stages of growth: egg, caterpillars, pupa and adults.

Eggs

A new cycle begins with the arrival of the adult butterfly. It is then ready to reproduce. The male butterfly flies over the Sea Lavender plants, in search of a female butterfly. This flying period last three to four weeks, from the end of July to mid-August, after which mating occurs. The female butterfly lays her eggs on a host plant called Salted-Meadow cordgrass. She can lay up to 24 eggs. The eggs hatch 10 to 24 days later.

Larva

After hatching, little caterpillars emerge and feed upon the Salt-Meadow cordgrass until the end of September. At this moment, the caterpillar stops feeding and buries itself at the base of the plant, where it spends winter and spring. The caterpillar is currently in diapauses. It will have to endure temperatures of -20ºC and periodic salt water flooding induced by storms. The caterpillar begins feeding on the Salt-Meadow cordgrass at the beginning of May until the end of the month. It then moults many times. At its 5th and final moult, which happens between mid-June and early July, the caterpillar is 2,3 cm in length and green with yellow longitudinal stripes.

Chrysalis

In the middle of the summer, the caterpillar gets ready for its nymphalid phase, a process during which the larval structures transform into adult ones. The caterpillar usually attaches itself on a stem of grass at the base of the Salt-Meadow cordgrass by means of a silk wad. It then changes into a chrysalis (or nymph). It is blue and green with black stripes. This phase lasts about 10 days.

Adult

The adult butterfly is completely formed when it emerges from the chrysalis between late July and mid August. Males appear first and start searching for a female. It is estimated that a male butterfly can travel up to 100 metres before finding a receptive female. They need to see to the reproduction of their species without wasting time because the adult butterfly’s lifespan is quite short. In fact, it lasts only one week.

Threats

The Maritime Ringlet faces many threats that may be of natural as well as anthropic origin, which means related to the presence of human beings. Firstly, whatever stage of the cycle the butterfly is in (egg, larva, chrysalis), neither is safe when storms hit. Each form is helpless against the force of flood water.

The Maritime Ringlet populations seem to vary every year. There is not one marsh’s population that fluctuates at the same time and in the same way. It is possible that flooding is the cause behind this observation. However, the population located near the Village Historique Acadien does not seem to have been disturbed by these same floods. On the contrary, this population is growing.

Ice is another factor that can easily interrupt the butterfly’s sensitive life cycle. When pushed into the marsh during a winter storm, it crushes the dormant larva, which contributes to the decrease of the butterfly’s numbers. The strong urban development surrounding the salt marsh is another threatening factor for the Maritime Ringlet because its habitat is directly affected by human activities. For example, in the past years, properties on the coastal stretch and around the salt marsh were greatly sought after. In addition to invading and trampling over the butterfly’s habitat, our actions may cause other problems such as physically altering the watershed, thus affecting the inflow and outflow of the marsh’s water. Consequently, the butterfly’s habitat is increasingly reduced and disturbed. Activities near the marsh accentuate the risk of water contamination with harmful products like oils, pesticides or detergents. Water pollution is a real threat to the butterfly’s larva and chrysalis.